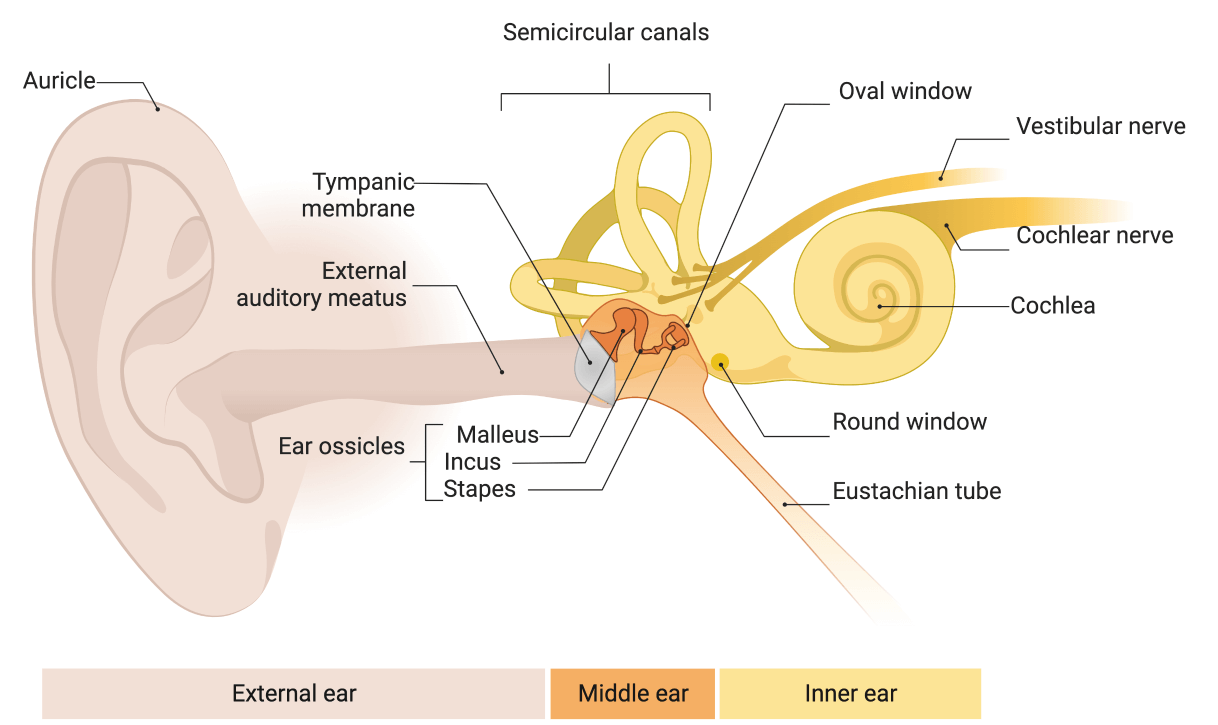

Human hearing system has three sections, the outer ear, middle ear and inner ear, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Sound waves are collected via Auricle and travel down the external auditory meatus where they cause the Tympanic membrane (eardrum) to vibrate. The vibrations of the Tympanic membrane are transferred through the middle ear’s ossicles to the cochlea in the inner ear. Inside the cochlea there are specialised sensory cells called hair cells. These are responsible for detecting vibrations in the cochlea and stimulating the cochlear nerve. The electrical signals in the cochlear nerve are sent through various processing centres to the part of the brain that analyses sound, where they are perceived as sound.

This diagram illustrates different sections of the auditory system.

Tinnitus is perception of sound without actual acoustic stimulation. People may perceive tinnitus as a sound coming from (1) inside one ear or both ears, (2) in the centre or back of the head or neck, or (3) as an outside sound from their environment. In other words, the individual is hearing a sound or combination of sounds (e.g., buzzing, ringing, whistle, or roaring sound) in the absence of such sounds being present in the environment or within their own body. This is called “subjective tinnitus”. Majority of people with tinnitus experience subjective tinnitus.

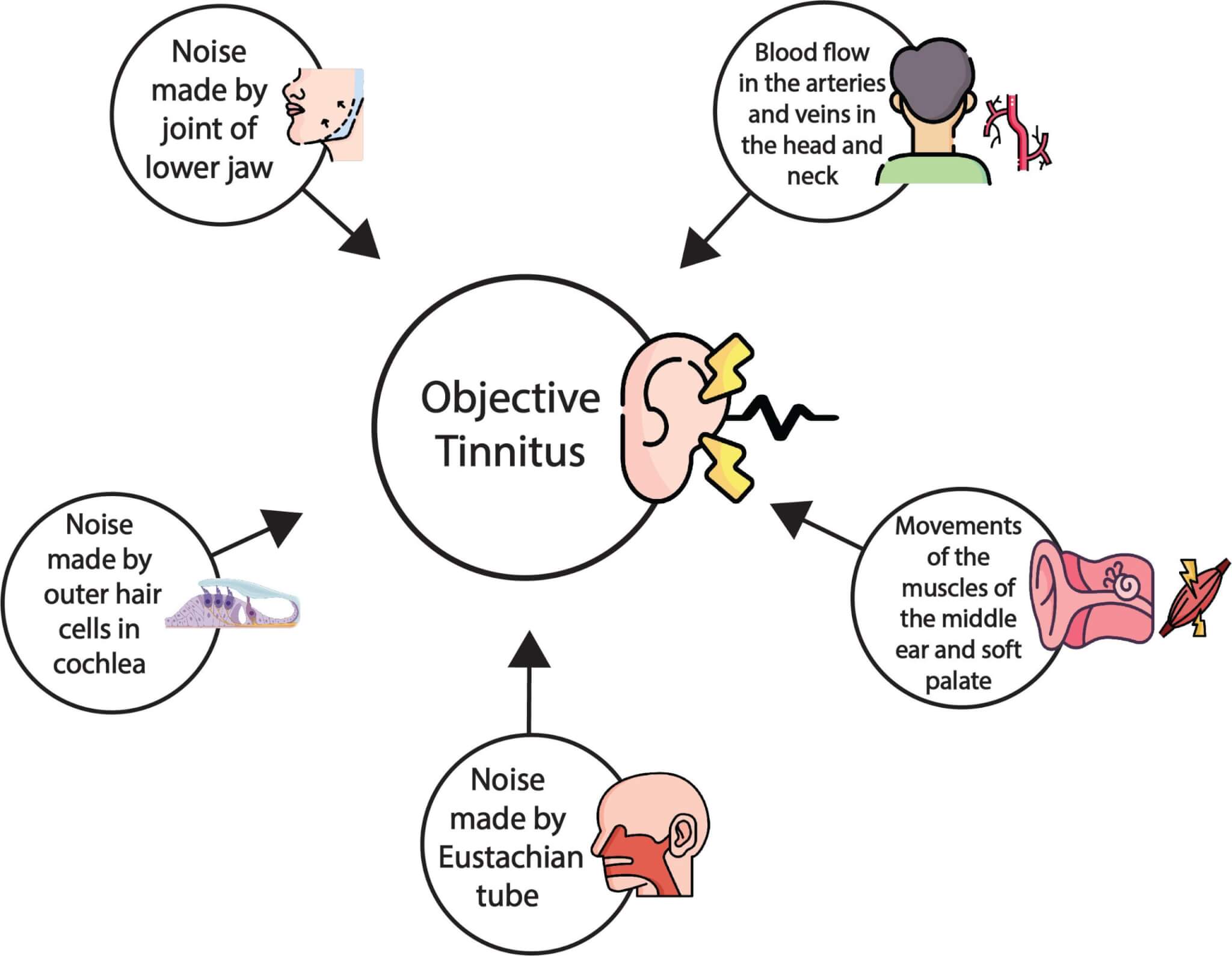

In small percentage of patients, tinnitus may arise from physical vibrations reaching the ear in which case it is called “objective tinnitus”. As shown in figure 2, tinnitus can be related to bodily sound sources such as: (1) blood flow in the arteries and veins in the head and neck; (2) movements of the muscles of the middle ear, and soft palate; (3) noise made by the tube that connects the inside of the eardrum to the throat (eustachian tube) or the joint that connects the lower jaw to skull (temporomandibular joint, also known as TMJ) ; (4) noise generated by outer hair cells inside the inner ear also known as “cochlea”.

This diagram illustrates different possible bodily sound sources for the “objective” tinnitus.

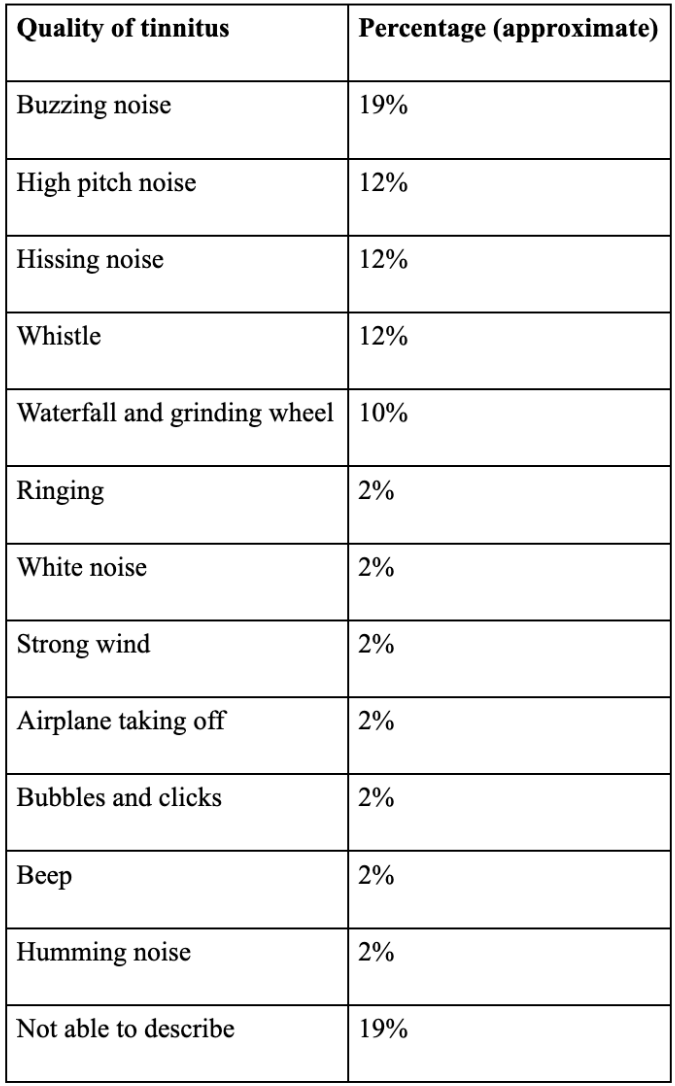

Tinnitus is estimated to occur in about 15% of the population, so approximately one billion people in the world have tinnitus. However, for many people, tinnitus occurs only intermittently, and it is not distressing. The perception of tinnitus can take many forms. See the Table below for descriptions of the quality of tinnitus given by some of our patients. It is worth mentioning that about 19% of patients are unable to describe what their tinnitus sounds like.

Table: Patients' descriptions of the quality of their tinnitus

Persistent tinnitus is diagnosed when tinnitus lasts for more than five minutes. The way that tinnitus is perceived over a prolonged period varies significantly from one person to another. Some possibilities are: (1) tinnitus is perceived all the time during waking hours; (2) tinnitus is perceived both during waking hours and in dreams; (3) tinnitus is not perceived all of the time, but is mainly perceived at nights or at quiet times during the day; (4) tinnitus is not always present, but when it comes it continues for varying durations ranging from a few hours to weeks.

It is worth mentioning that no particular pattern is easier or more difficult to manage than others. The impact of tinnitus on the person’s life is not directly linked with the pattern of tinnitus persistency nor with its loudness. Research studies conducted at Hashir International Specialist Clinics and Research Institute for Misophonia, Tinnitus & Hyperacusis concluded that the impact of tinnitus on the person’s life is directly linked with the amount of annoyance and anxiety that it causes. With the help of therapy, patients can learn to identify and modify the process in which tinnitus leads to annoyance and anxiety. Recent research published in the American Journal of Audiology by Dr Hashir Aazh and his collaborators from Universities of Cambridge, Melbourne and Florida Atlantic showed that specialist tinnitus rehabilitation programme based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) helped patients to reduced anxiety and annoyance caused by tinnitus and minimise the impact of tinnitus on their life without any significant changes in the actual persistency pattern or the loudness of tinnitus. In other words, when people learn to manage tinnitus-related anxiety and annoyance using CBT skills, tinnitus (with the same loudness and persistency) has less impact on their life. When the impact of tinnitus on the person’s life reduces, tinnitus gradually loses its significance and makes it more likely to fade away into the background (a process known as habituation) as opposed to be at the foreground of their attention.

Tinnitus does not hamper the individual’s ability to detect and discriminate external sounds, even when the sounds are like their own tinnitus. A study conducted in 2020 by Dr Fan-Gang Zeng and colleagues at the Centre for Hearing Research at the University of California Irvine, USA, showed that tinnitus does not interfere with perception of external sounds. Individuals with tinnitus could detect and discriminate sounds as well as people in a control group with no tinnitus.

In majority of the patients, tinnitus is not related to any known disease. In some patients, tinnitus may be related to disorders of the auditory system and/or certain environmental exposures. In most of the causes listed below tinnitus is combined with hearing loss. Some of the causes of tinnitus combined with hearing loss are listed below:

For most people with tinnitus, none of the above-mentioned ear and hearing disorders appear to be present. However, it is important to see an ENT specialist and audiologist in order to exclude these.

Distorted hearing is often reported by those with tinnitus, especially musicians. Distorted hearing can be independent from tinnitus. However, for some people distorted hearing may be partly related to their tinnitus, in which case therapy for tinnitus may also reduce the distortion of hearing. Auditory processing disorder (APD) is defined as difficulty in the perception of speech and non-speech sounds without any marked loss of hearing sensitivity to weak sounds. APD often co-exists with speech and language problems, dyslexia (difficulty reading, writing, spelling), and memory or attention disorders. People with APD often have difficulty hearing in noise. APD can co-exist with tinnitus. To learn more about APD click here.

Tension in the head and face muscles can lead to headaches. A recent study conducted by Dr Lugo and colleagues in Sweden showed that the prevalence of headaches among people with tinnitus was 26% and it reached 40% for people with severe tinnitus. The headaches may be related to the stress and anxiety caused by tinnitus, or they may be related to a pre-existing problem like migraine. If the former is the case, then therapy for tinnitus may reduce the incidence and/or severity of headaches. If the latter is the case, then a doctor may be able to diagnosis the root cause of the headaches.

There are tiny muscles attached to the ossicles in the middle ear. If the muscles of the middle ear contract, then they stiffen the ossicular chain, leading to a reduction in the transmission of sound from the eardrum to the cochlea. This occurs as a natural reflex when we are exposed to an intense sound; it helps to protect the delicate structures inside the cochlea. The muscles relax when the intense sounds stop. However, sometimes the muscles can contract for a long time without any intense sound being present. This can lead to a sense of aural fullness and perception of hearing difficulties. Often the muscles relax during therapy for tinnitus, and such aural fullness disappears. Aural fullness can also occur with ear disorders that affect the cochlea (e.g. Ménière's disease), middle ear (e.g. otitis media, and infection of the middle ear), or hearing loss. These will usually be detected when you see an ENT specialist prior to any therapy.

Tinnitus distress can be associated with hyperacusis or oversensitivity to sound. Hyperacusis is intolerance to certain everyday sounds, which are perceived as too loud or uncomfortable, causing significant distress and impairment in the individual's day-to-day activities. The underlying mechanism for this is not clear. However, fear of worsening of tinnitus due to noise exposure is thought to be one contributing factor. The individual may feel (perhaps unconsciously) that they need to prevent their tinnitus from getting worse by avoiding certain sounds in the environment. This condition is also known as tinnitus-induced hyperacusis, and it is more common in people with what is called “reactive tinnitus”. This term is used to describe tinnitus whose loudness or pitch changes in response to external sounds. Reactive tinnitus is more common among musicians than among non-musicians, but it is not limited to musicians. Both hyperacusis and tinnitus could be related to how our brain responds to damage to the auditory system. How our brain responds depends partly on cognitive and emotional factors. CBT can help to modify the way that our brain responds to damage to the auditory system.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression are common among individuals with tinnitus. However, not everyone with tinnitus who exhibits such symptoms is diagnosed with anxiety or mood disorders when undergoing formal psychological evaluations. It is understandable that tinnitus might make us feel anxious or experience a low mood. A history of mental illness increases the likelihood of a person feeling anxious or depressed should they develop tinnitus.

For individuals who suffer from tinnitus, depressive symptoms may be alleviated if tinnitus-induced anxiety are managed adequately, even if the tinnitus loudness remains unchanged.

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) are defined as exposures to different forms of abuse (physical, emotional and sexual) and family dysfunction (substance abuse, mental illness, mother treated violently, incarcerated household member, and parental separation). Parental separation and poor parental mental health are important forms of ACEs with prevalence of about 23% and 19%, respectively. There may be a relationship between ACE and poor mental health in later life. There are several research studies suggesting that ACE can affect the way that a person responds to stress later in life .

In a series of studies conducted at our clinics, we explored the relationships between parental mental health and parental separation in childhood and the psychological impact of tinnitus on the individual in their adulthood. The results showed that parental separation in childhood was not associated with a higher risk of being affected by tinnitus in adulthood. However, for those who did develop tinnitus, poor parental mental health in childhood was significantly associated with an increased risk of tinnitus-related depression, suicidal and self-harm thoughts, and sleep difficulties. In other words, people whose parents suffered from anxiety, depression, and other psychological disorders had a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts and sleep disturbances if they developed tinnitus later on in life. This highlights the importance of mental health for our wellbeing as well as for giving our children psychological strength in dealing with stress later in life.

Tinnitus is often associated with difficulties in initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, going back to sleep if woken up in the middle of the night, and achieving restorative sleep. About 70% of patients seeking help for tinnitus report some form of sleep difficulty.

In a study conducted in our clinic in collaboration with the University of Nottingham, we explored the associated between tinnitus loudness and sleep disturbances based on data for 417 patients. The analysis showed that the loudness of tinnitus is only indirectly related to the severity of insomnia. In other words, louder tinnitus does not necessarily lead to more sleep disturbances. The severity of insomnia depends on the amount of depression and annoyance caused by the tinnitus. The more depressed and annoyed a person becomes, due to their tinnitus, the more sleep disturbances they tend to experience. According to the theory behind CBT, our emotional disturbances such as feeling irritated or depressed are not directly due to hearing tinnitus, but rather are the result of our thoughts and behaviours. Therefore, in order to reduce tinnitus-related sleep disturbances, we need to manage our thought processes and minimise avoidance behaviours. This is the aim of CBT for tinnitus. Listening to music or background noise at night time is an avoidance behaviour and it does not address the key cause of the sleep disturbances, namely the tinnitus-related negative thoughts.

In addition to difficulties in initiating sleep or going back to sleep if woken up in the middle of the night, some people complain that tinnitus wakes them up and disturbs their sleep. If tinnitus wakes people up, then it should be perceived during sleep. It is not unusual to have some sensory experiences reflected in dreams, and auditory experiences in dreams are common. Auditory sensations occur in over 50% of all dream reports, while olfactory and gustatory sensations occur in approximately 1% of all dream reports. However, during sleep, awareness of external auditory stimuli is typically reduced. In a recent study conducted in our clinic we found that 5% of tinnitus patients reported hearing tinnitus in their dreams. The impact of tinnitus on the patients’ lives was greater for patients who reported hearing tinnitus in their dreams than for those who did not. People who reported hearing tinnitus in their dreams were affected almost twice as much by their tinnitus as people who did not. This may have happened because the content of dreams tends to reflect events and things that are on a person’s mind, so people whose tinnitus has a large impact are more preoccupied by it and are more likely to dream about it. For such people, it is possible that tinnitus wakes them up. However, they constitute only a small minority of people seeking help for tinnitus.

Is it also possible that when a person wakes up at night and interprets this as being due to their tinnitus it is being caused by “exploding head syndrome” (EHS)? EHS was first described by Dr Robert Armstrong Jones who referred to it as “a snapping of the brain”. EHS is often characterised by the individual hearing a sudden loud noise or having a sense of explosion in their head just before drifting off to sleep or just before waking up. About 8% of tinnitus patients attending our clinic reported EHS. However, EHS does not seem to be related to tinnitus, and if you feel that you are bothered by repetitive occurrences of EHS then you may need to see a psychiatrist or sleep specialist for further assessment and treatment (when needed).

There is no treatment that has been proved to “cure” tinnitus. However, there are several methods that have been used for tinnitus management with various degrees of success ranging from sound therapy and masking machines to mindfulness and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). To date, CBT is the most evidence-based intervention for tinnitus management . At Hashir International Specialist Clinics, we offer a specialised tinnitus rehabilitation programme based on CBT. CBT helps to understand and manage the emotional, cognitive, and behavioural processes that are often linked to the experience of tinnitus. This helps to alleviate anxiety, stress, anger, and depressive symptoms by helping the patient to modify their dysfunctional cognitions, ruminations, and safety-seeking behaviours.

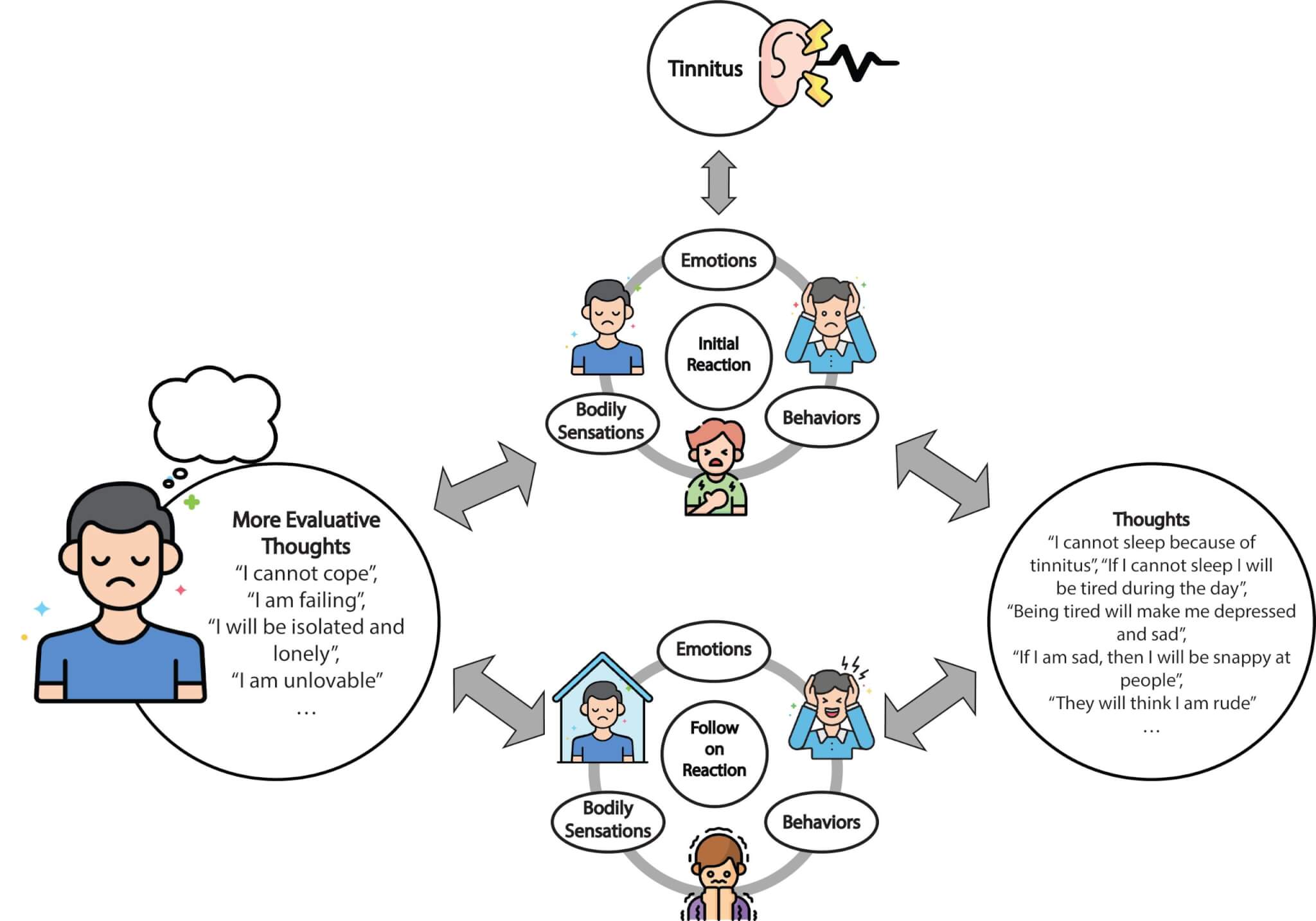

Dr Aazh’s CBT model that explains the experience of distressing tinnitus.

Over the last decade, Dr Hashir Aazh and his associates have developed several different CBT models for tinnitus distress. The models have been modified and have evolved based on experiences in clinical practice so as to be more relevant to the experience of distressing tinnitus as opposed to general anxiety. Also, the models have been modified so that they can be applicable to the majority of people experiencing distressing tinnitus. In their most recent model (shown in the diagram above), they conceptualised the distress caused by tinnitus in the following way (Figure 3). Perceiving tinnitus creates an initial reaction that includes an emotional component (e.g., feeling upset or irritated), bodily sensations (e.g., tightness in chest, or feeling fullness in the ears), and a behavioural component (e.g., rubbing your ears). These components are not necessarily triggered by conscious thinking. There are many studies suggesting that the early sensory processing of stimuli is influenced by the emotional significance of those stimuli. This is also the case for certain bodily sensations that often accompany emotions. Certain behaviours can also happen without conscious thinking. Conscious thinking starts after the initial reactions to the triggers and may lead to escalation of the reactions. These thoughts are called automatic thoughts. An example of an automatic thought is “I will not be able to sleep tonight”.

The follow-on reactions may also have components related to emotions (e.g., fear or disappointment), behaviour (e.g., using background noise to avoid hearing tinnitus, self-isolation and avoid going to certain places in the fear that tinnitus might get worse, or reassurance seeking) and bodily sensations (tension or palpitations). The follow-on reactions may lead to further negative thoughts and confirm negative beliefs. These thoughts will feed back to the reactions, creating the vicious cycle of distress. When the vicious cycle forms, this makes it harder for our brain to put tinnitus into the background; instead, we focus on it even more. The aim of CBT is to break this vicious cycle by teaching the individual skills to help them (1) to identify their thoughts and behaviours, (2) assess if they are helpful or counter-productive, and (3) to change their unhelpful thoughts and modify their avoidance behaviours if needed.

CBT is not aimed at reducing the perception of tinnitus. Rather, the goal is to break the vicious cycle illustrated in the CBT model, which is triggered by tinnitus. Over the last 2 decades, Dr Hashir Aazh and his associates have developed a specialist programme of tinnitus rehabilitation based on CBT comprising 14 therapy sessions (via video calls) comprising four stages: I) Assessment, II) Preparation, III) Active treatment, and IV) Maintenance stage. The content of the therapy briefly comprises (1) education about tinnitus and relevance of CBT, (2) enhancing patient’s motivation to engage with the therapy process, (3) setting goals, (4) formulation, (5) identifying troublesome thoughts, (6) identifying avoidance behaviours and rituals, (7) SEL (Stop Avoidance, Exposure, & Learn from it), (8) KKIS (Know, Keep on, Identify, Substitute), (9) identify and challenge deeper thoughts and beliefs, and (10) integrating CBT into lifestyle (CBStyle). A recent study conducted by an international group of experts from the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and the UK, which was published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2020), assessed the effect of CBT on tinnitus. The authors included 28 studies on CBT for tinnitus with a total of 2733 participants. The conclusion was that CBT was effective in reducing the negative impact of tinnitus on the patients’ quality of life. Indeed, most researchers are of the opinion that the evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT as a treatment for tinnitus distress is stronger than the evidence supporting any other form of treatment. However, CBT was usually not found to reduce the loudness of tinnitus. CBT can be effective when delivered in various formats (for example, individual face-to-face, group setting and via video).

Aazh, H. (2023). What is Tinnitus? Available at: https://hashirtinnitusclinic.com/tinnitus/ (Accessed: Day Month Year)