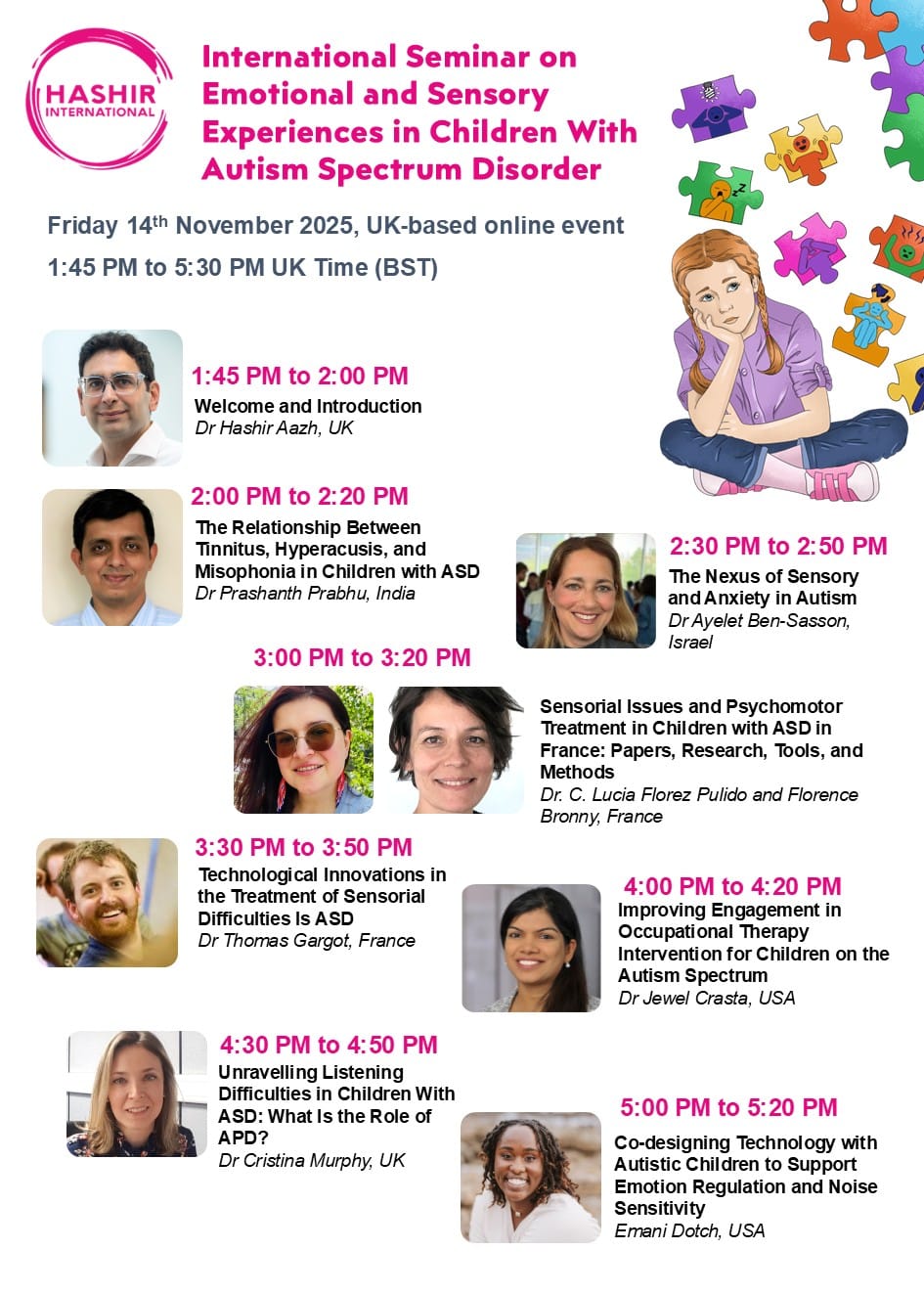

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) often experience the world through a sensory lens that is more intense, unpredictable and emotionally demanding than that of their peers. Sounds, textures, movements and social environments that are manageable for most children can quickly become overwhelming for others. These sensory experiences shape emotions, behaviour and participation in ways that families, teachers and clinicians witness every day. The First International Seminar on Emotional and Sensory Experiences in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder took place online on 14 November and brought together approximately 200 professionals and parents from across the world. The event was organised by Hashir International Institute, a UK based independent research institute and specialist clinic for sound intolerance disorders. Participants included audiologists, occupational therapists, psychomotor therapists, researchers, teachers, speech and language therapists, mental health professionals and caregivers. The shared goal across disciplines was to deepen understanding of the lived sensory and emotional experiences of children with ASD and to improve support through collaboration rather than isolated expertise.

Across the seminar, eight themes emerged that help explain how children experience the world and how professionals and families can support them most effectively. Each theme contributes to an integrated understanding of how sensory and emotional wellbeing create the foundation for participation, confidence and connection.

Theme 1: The Sensory and Anxiety Loop

The opening theme was delivered by Dr Ayelet Ben-Sasson, Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Haifa, Israel, who explained that sensory over responsivity and anxiety are not separate difficulties. They develop together and influence one another. Many children with ASD show strong physical reactions to sound, touch or movement before conscious thought takes place. According to Ben-Sasson’s research findings, these responses are not intentional and are not under voluntary control. She illustrated this point with the example of a child who froze every morning at the entrance to his classroom, covering his ears, crying and refusing to enter. The reaction was not a behavioural refusal but a sensory fear triggered by noise, touch and unpredictability before he had time to think. As she described it, the nervous system reacts before the child has words.

Ben-Sasson said, “For many children, sensory experiences construct the emotional meaning of the world. If the world feels unpredictable or threatening on a sensory level, avoidance or withdrawal becomes an expression of fear rather than unwillingness.”

The theme demonstrated that emotional regulation for children with ASD must address sensory experience directly. Progress is more likely when adults recognise that behaviour often reflects an instinctive attempt to stay safe rather than a deliberate choice to disengage.

Theme 2: Hyperacusis and Misophonia in ASD

Sound intolerance was a central topic across the seminar. Hyperacusis and misophonia are particularly common among children with ASD and can significantly interfere with daily activities, family routines and participation in education. Hyperacusis refers to heightened loudness perception, in which ordinary sounds such as playground noise or household appliances are experienced as excessively loud, uncomfortable or painful. Misophonia involves strong negative emotional responses to specific human generated or repetitive sounds such as chewing, breathing or tapping. In both conditions, the auditory signal triggers emotional and behavioural reactions before conscious reasoning.

At the Hashir International Institute, diagnosis is made through structured clinical interviews during audiology assessments to determine whether reduced sound tolerance significantly disrupts daily life. A clinical example helped illustrate this. A seven-year-old boy with ASD isolated himself during family mealtimes and frequently asked others to stop chewing. At first, his family interpreted this as rudeness or anger. However, assessment revealed that chewing sounds triggered intense emotional discomfort that led to avoidance. The behaviour was not aggression. It was protection.

Research suggests that hyperacusis affects more than 40 percent of children with ASD and more than 60 percent across the lifespan. Misophonia affects an estimated 13 to 36 percent. These figures indicate that sound intolerance is not a rare or niche problem but a core issue for many children with ASD. Understanding sound intolerance allows teachers and families to respond more compassionately and effectively. When sound driven behaviour is interpreted as distress rather than disobedience, conflict decreases and support becomes possible.

As the discussion outlined, diagnostic clarity is not a label. It is a foundation that allows children to receive support that matches the nature of their difficulty.

Theme 3: CBT Delivered by Audiologists and Occupational Therapists for Hyperacusis and Misophonia

The seminar highlighted CBT informed therapy as an evidence based approach to support children with hyperacusis and misophonia. The presentation by Dr Hashir Aazh, Hashir International Institute, London, UK, described how cognitive behavioural therapy can be adapted for children with ASD by combining emotional understanding and sensory strategies. Exposure to sound alone is rarely helpful and can cause further distress if the nervous system is not ready. Likewise, cognitive reframing without attention to sensory processing can feel abstract or irrelevant to younger children. Therapy is most effective when both elements are delivered in a developmentally meaningful way.

This often begins with playful and symbolic activities that help the child understand their reactions to sound in emotional rather than intellectual language. Drawings, stories and toys allow children to represent sounds and their responses without shame. Parents frequently report that improvements in sound tolerance emerge in parallel with improvements in confidence and willingness to participate in activities.

During this section of the seminar, the quote was included that reflected the philosophy of this approach. Our director, Dr Hashir Aazh said, “CBT for hyperacusis and misophonia is not about teaching children to tolerate distress. It is about helping them feel safe so that the sensory system can gradually relearn comfort.”

The discussion recognised that CBT is not limited to mental health professionals. Occupational therapists and audiologists have successfully integrated CBT principles into intervention for sound intolerance by pairing sensory self regulation strategies with graded exposure and cognitive reframing through meaningful activity. The most powerful therapeutic outcomes were not described as tolerating sound. They were described as re entering daily life.

Theme 4: The Body as the Foundation of Emotional Experience

The joint presentation by Dr C. Lucia Flórez Pulido, Centre Médico-Psycho-Pédagogique (CMPP) Ivry-sur-Seine, Private Practice Paris, Syndicat National d’Union des Psychomotriciens (SNUP, Scientific Council Member), Respir Formation (Trainer), ABSM André Bullinger (Trainer and Member), France, and Florence Bronny, Psychomotor Therapist and President of the Syndicat National d’Union des Psychomotriciens (SNUP), Respir Formation Director and affiliated with the Vertigo and Balance Research Institute (IREV, CNRS), France, focused on the role of the body in shaping emotional experience. Many children with ASD experience challenges in the vestibular, proprioceptive and tactile systems. These challenges influence balance, posture, comfort in physical space and readiness for social engagement. When the body does not feel grounded or safe, the world feels unpredictable. Children may limit movement, avoid social play or become cautious in environments that appear benign to others.

The speakers described psychomotor therapy as a process of supporting children to feel physically secure, rhythmic and confident. Through regulated movement, postural support and shared physical play, children learn to inhabit their bodies with confidence. Once physical safety is re established, curiosity and social participation increase naturally. Bronny said, “When postural security is restored, the child can access the world rather than defend against it.”

This theme resonated strongly with occupational therapists who frequently observe that a stable sensory motor foundation is essential for emotional regulation and social connection.

Theme 5: Technology as a Scaffold for Participation

Technology was discussed as a way of supporting participation rather than replacing human interaction. Dr Thomas Gargot, Associate Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of Tours, France, presented on the use of robotics and virtual reality in therapeutic contexts. Robots provide predictable, structured and non judgemental social interactions, while virtual reality offers controlled environments in which children can practise coping strategies with a clear sense of control.

Technology is most powerful when it acts as a bridge between safety and participation. Children who find direct social interaction overwhelming may first interact comfortably with robots and then gradually transfer confidence to peer relationships. Virtual reality can allow practice with sensory triggers in a gradual and controlled way before facing them in the real world. Gargot said, “Technology does not replace connection. It prepares the nervous system for connection by offering predictability.”

This theme demonstrated that when used thoughtfully, technology can lower emotional and sensory risks while motivating engagement and learning.

Theme 6: Participation Through Motivation and Meaning

Participation is both the vehicle and the outcome of successful intervention. Dr Jewel Crasta, Occupational Therapy Division, The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA, emphasised that motivation and meaning are not rewards for regulation. They are the drivers of regulation. Children regulate more effectively when they are engaged in activities that reflect their interests, values and sense of identity. When therapy is structured around what matters to the child, instead of requiring regulation as a prerequisite to access meaningful activity, emotional stability follows more readily.

One example involved a child who loved art but became overwhelmed in group settings. Therapy began with supported individual art sessions to strengthen joy and autonomy in the activity. Over time, the child chose to join group art activities. Crasta said, “Participation is not the final step in therapy. Participation is the pathway to therapy.”

This theme reinforced the idea that therapeutic progress is greatest when intervention feels meaningful rather than imposed.

Theme 7: Auditory Processing Disorder and Listening Fatigue

Auditory Processing Disorder in ASD was explored by Dr Cristina Murphy, The APD Clinic, 10 Harley Street, London, UK. Children with APD can have typical hearing thresholds yet still struggle to understand speech in noisy environments because their brains cannot separate the relevant signal from competing sounds. This difficulty leads to listening fatigue, frustration, apparent inattention and emotional shutdown.

APD often becomes most visible in the classroom, where auditory demands are highest. Children may appear to lose interest or stop responding but are actually overwhelmed by cognitive and auditory load. Murphy said, “Listening can be exhausting. When the brain must work overtime to extract meaning from noise, the child may run out of capacity long before others notice.”

Effective support includes reducing noise levels where possible, adding visual supports, increasing predictability during transitions and allowing children to pause before overload occurs. Families often feel relief when APD is identified because the diagnosis reflects the lived experience they have been trying to describe.

Theme 8: Co Design and Listening to Children

The final theme of the seminar emphasised that children with ASD know a great deal about their own sensory needs when they are given space to express them. Emani Hicks, Department of Informatics, University of California, Irvine, USA, described methods to allow children to communicate sensory preferences through drawings, icons, gestures and technology. When children create their own coping tools or environmental adaptations, the strategies tend to be more precise and effective than those designed entirely by adults.

Hicks said, “Children do not resist support. They resist support that does not match their sensory experience.”

Examples described included children designing hand signals to request a break from noise, creating personal calm kits to use at school or mapping out safe sensory zones in classroom environments. The message was that when children participate in designing their support, intervention becomes empowering, respectful and developmentally positive.

Shared Principles Across All Sessions

Although each speaker approached the topic from a different clinical perspective, a number of shared principles emerged across presentations. Sensory and emotional processes are deeply connected and cannot be successfully addressed in isolation. Behaviour is often a communication of overwhelm rather than an expression of opposition. Children participate most successfully when they feel safe physically and emotionally. Intervention is most effective when it is meaningful and relevant to the child rather than imposed. Progress is most consistent when professionals collaborate across disciplines rather than competing for conceptual priority. The child’s voice is essential in shaping intervention.

These principles provide a foundation for compassionate and clinically grounded support for children with ASD.

Support for Families and Professionals

Families and clinicians frequently request follow up resources to support children with sound intolerance conditions such as hyperacusis, misophonia and Auditory Processing Disorder. Hashir International Institute provides multidisciplinary assessment and therapy that combines audiology, occupational therapy and CBT informed approaches tailored to the needs of children with ASD. Further information is available at www.hashirinternational.com.

Closing Reflection

Children with ASD do not need to be pushed to cope with the world. They need environments and relationships that help them feel safe, confident and respected. When sensory experiences, emotional needs and participation goals are addressed together, children expand their world instead of shrinking away from it. The seminar demonstrated what becomes possible when families, professionals and researchers collaborate and when children are seen as experts in their own sensory experiences.